A stroll down a dark memory lane

The Bayern Quarter is an unassuming neighbourhood, most known for JFK’s iconic 1963 speech where he proudly declared he was a jam donut. Stepping out of the subway station onto a busy street in Schöneberg, you will see a smallish but rather lovely park area with benches and trees across the road.

Jewish Switzerland

Before Hitler was appointed in 1933, this area was often referred to in Berlin slang as ‘Jewish Switzerland’ because so many wealthy intellectual Jewish families lived in the area. Doctors, lawyers, politicians, even Albert Einstein lived here during his time as a professor at Humboldt University. Like many of the fully integrated German Jews, these people usually considered themselves as German first, Jewish second and often occupied prominent positions amongst the intellectual elite of Berlin. But even this relative status could not protect them after the National Socialist movement took power.

Dispossession and deportation

More than 6000 people were deported from this quarter. Houses forcibly taken from their owners, with many more forced to sell for a pittance. Forced to live in cramped communal houses and forbidden to work in their professions, the laws against Jewish participation in daily life grew more and more restrictive until they were simply deported to camps, right beneath the noses of supposed ‘aryan’ citizens. Of course, this is not unique to Schöneberg and the Bayern Quarter. Jews lived fully integrated throughout Berlin and this pattern was repeated over and over. However, what makes this area unique today is the style of remembrance and memorial chosen to grace the streets here. Now, Berlin is full of memorials. Sometimes it feels as though there are memorials on every street corner and to a certain extent Berliners have to battle a degree of ‘memorial fatigue’. However the memorial here on these streets around Bayersisches Platz never ceases to schock and silence me and the many guests I bring here to witness.

A decentralised remembrance

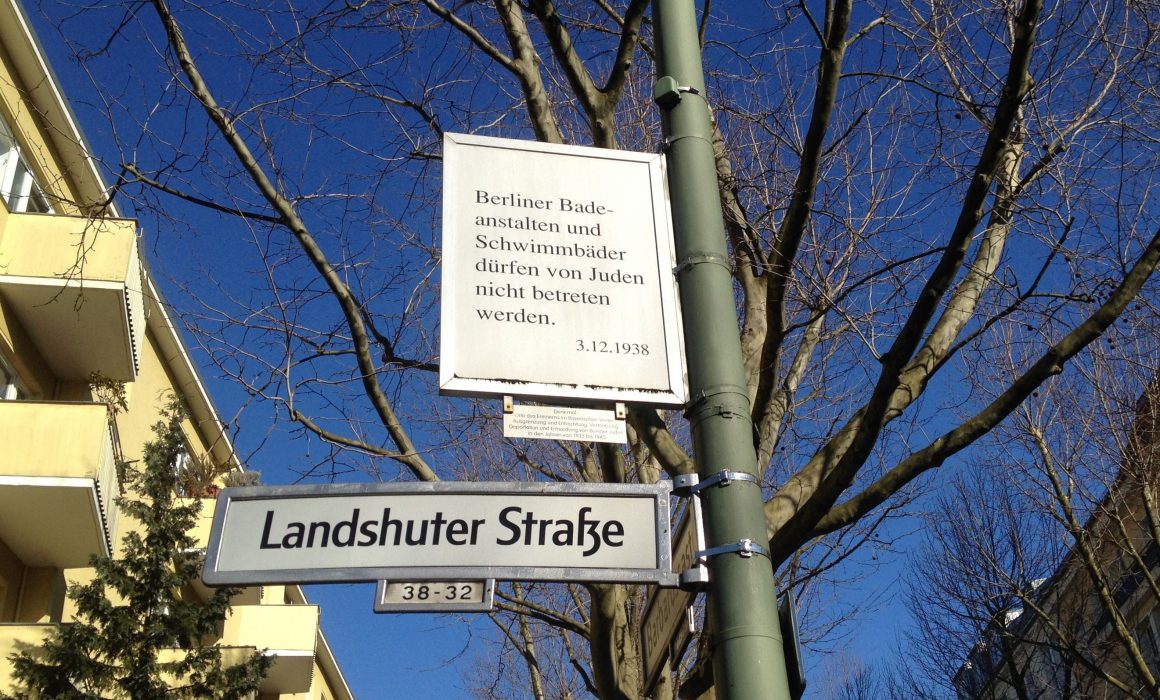

Installed in 1993 by the artist Renata Stih and historian Frieder Schnock it consists of 80 individual plaques suspended from the street lamps. Each plaque has a picture on one side, and a statement or quote on the other. The pictures themselves are rather innocuous. A loaf of bread. A pair of swimming trunks. A newspaper. But on the other side are words which track a chilling progression of laws stripping the Jewish people of their basic human rights, including forbidding them to flee the very persecution which threatened to destroy them. Laws, decrees and commonly accepted rules are listed here. Jews are only allowed to sit on benches marked with yellow. Jews may not enter pubic swimming pools. Jews may no longer own a radio. Jews must surrender all valuables such as Jewellery. Jewish actors may not perform. Jewish and Aryan children may not play together. On and on it goes. Tracking the seemingly endless parade of humiliations and restrictions which the Jews had to face. On and on. It gets worse and worse. It is relentless. And yet how much more relentless was it for the Jews who lived here at the time. The experience of walking the streets here and reading the signs is a little like chinese water torture. Each sign in itself is only a droplet, yet taken one after another after another after another the effect is overwhelming, hammering home the extreme abuse of the Jews which led literally to their deaths. As a non-Jew the sense of shame I feel when I read these signs is huge. How could this have happened? How could people like me have let this happen? On their doorstep?

Confrontation rather than forgetting

This memorial – on almost every street corner in this area – is yet another way the Germans are confronted by their past at every turn and is yet another example of how Germany as a nation has lead the way in the culture of Holocaust remembrance. And yet.

And yet. Last month a public swimming pool in Germany (though not in Berlin admittedly) stated that muslim men would no longer be admitted (or at least men of muslim appearance). Perhaps we all need to look again and again at these signs in the Bayerisches Viertal.